D3.js is a pretty neat technology for building data visualizations. Some of my favorite examples include Mike Bostock’s “Is it better to rent or buy?” in the New York Times, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation GBD Compare tool, and the effective distance visualization for epidemiological modeling built by Dirk Brockman and the Research on Complex Systems lab. These examples behave how users expect them to: they are fast, interactive and load directly in the browser without a plugin. The broad variety of examples on display at Mike Bostock’s site show just how customizable this tool is.

Unfortunately, this potential for customization comes at a cost — there is a fairly steep learning curve relative to other visualization tools. I found Scott Murray’s tutorials very helpful, and am currently working through his book. Here are a few issues I ran into during my learning process.

Callbacks

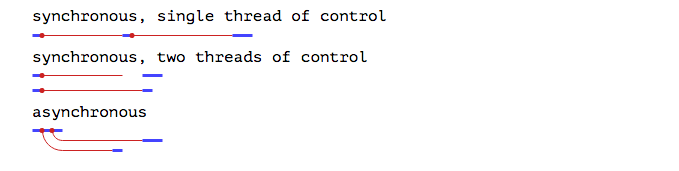

Coming from a background programming in Python, I wasn’t aware that many JavaScript functions are asynchronous. This property of the language is probably due to JavaScript’s origins in the browser. An entire webpage can’t wait for a single script to load, so the asynchronous nature of JavaScript allows other code to run while a different process is finishing up or waiting for a response.

Asynchronous code can be somewhat mind-bending, but I found this introduction from Max Ogden’s The Art of Node particularly helpful. I initially ran into trouble when importing a CSV file using the asynchronous d3.csv method, but this stackoverflow answer by Mike Bostock helped clear things up:

d3.csv is an asynchronous method. This means that code inside the callback function is run when the data is loaded, but code after and outside the callback function will be run immediately after the request is made, when the data is not yet available. In other words:

first();

d3.csv("path/to/file.csv", function(rows) {

third();

});

second();If you want to use the data that is loaded by d3.csv, you need to put that code inside the callback function (where third is, above):

d3.csv("path/to/file.csv", function(rows) {

doSomethingWithRows(rows);

});

function doSomethingWithRows(rows) {

// do something with rows

}He also outlines a few other ways to use the data in this answer, so it’s worth a look.

Functional Programming

Arrays in JavaScript have many useful built-in methods, including map, filter, reduce, and forEach. These methods are very helpful for processing incoming data whether from a CSV, TSV or JSON file type. The end result is more concise code, although there might be small (probably insignificant) performance losses.

I found Eloquent JavaScript chapter on higher-order functions helpful in learning the details of these methods. For extra practice, try the Object Oriented and Functional Programming exercises from Free Code Camp. The MDN documentation is a good reference as well.

Ok, now what?

Once you have your data loaded and in the format that you want, you need to do something with it. With D3, you bind data to elements on the page by selecting the elements, counting and parsing your dataset using the data method and then appending each value to an element.

One confusing part of this process is that it is possible to select elements even if they don’t exist yet. Here’s an example:

var dataset = [ 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 ];

d3.select("body").selectAll("p")

.data(dataset)

.enter()

.append("p")

.text(function(d) {return d;} ); In the above example, the selectAll method will return an empty selection if no paragraphs exist yet in the body. This isn’t a problem, however, because after the data method parses and counts the data, the enter method creates placeholder elements for each value in the dataset that can then be operated on by the remaining methods.

In this case, the append method then inserts a paragraph element into the DOM for each placeholder element, and inserts the corresponding numeric value from the dataset for each element using the text method. The end result will be an HTML body with five paragraphs, each containing a value from the dataset.

For a more in-depth explanation, see Scott Murray’s tutorial.

Reversed Coordinate System

The SVG coordinate system starts at the top left corner of the element, with a positive y-coordinate moving downwards a positive x-coordinate moving to the right. This is a little backwards, so you need to transform the data in order to plot standard x,y coordinates. In this case, all you have to do is switch two values when you set the y-scale of the plot.

var h = 400; //The height of the SVG

var yScale = d3.scale.linear()

.domain([0, d3.max(dataset, function(d) { return d[1]; })])

.range([h, 0]);In this case, all we had to do was switch the output range from [0, h] to [h, 0], and D3 will take care of the rest when this scaling function is used on each piece of y-coordinate data.

A detailed walkthrough of this topic is available here.

Building Axes

The SVG is a blank canvas, so if you want axes on your chart, you need to specifically define them. In D3, the axes are actually functions, and they draw on the canvas when they are called. So, to start out, you would use the d3.svg.axis method to build an axis function:

var xAxis = d3.svg.axis()

.scale(xScale)

.orient("bottom");Note that you pass a predefined xScale function into the scale method so that the x-axis tick marks match your data.

Next, you call that axis function, appending it to the page:

svg.append("g")

.attr("transform", "translate(0," + (h - 30) + ")")

.call(xAxis);Using the call method draws the axis, and the transform attribute moves the axis to the bottom of the plot.

Finito

Ok, that’s it for now. Hopefully this post helps clarify some of these issues, or points you towards some good resources for learning more. Although it can be difficult at the beginning, this complexity will be a benefit later on when you want to build a custom visualization.