If you’re hoping to do good in the world, it makes sense to ask where your efforts will make the biggest impact. Some have claimed that high risk, high return projects are most promising because those areas are less crowded. For example, here’s a quote from Robert Reich’s essay on the role of philanthropic foundations in society:

When it comes to the ongoing work of experimentation, foundations have a structural advantage over market and state institutions: a longer time horizon. Once more, the lack of accountability may be a surprising advantage. . . foundations are not subject to earnings reports, impatient investors or stockholders, or short-term election cycles. Foundations, answerable only to the diverse preferences and ideas of their donors, with a protected endowment permitted to exist in perpetuity, may be uniquely situated to engage in the sort of high-risk, long-run policy innovation and experimentation that is healthy in a democratic society.

The Open Philanthropy Project outlines a similar approach in a post about their giving philosophy:

One of our core values is our tolerance for philanthropic “risk.” Our overarching goal is to do as much good as we can, and as part of that, we’re open to supporting work that has a high risk of failing to accomplish its goals. We’re even open to supporting work that is more than 90% likely to fail, as long as the overall expected value is high enough.

It seems intuitive that there are returns to risk taking but I was wondering if there were any datasets out there that would support this idea. Below I attempt to answer this question by looking at evidence from science, philanthropy, and public policy. I just finished a meta-analysis that combines the interventions from below that have similar units, so take a look at that as well.

Definitions

Before I continue, I think it makes sense to define the terms risk and return. By return, I mean the impact of an intervention using units like disability adjusted life years per dollar, benefit to cost ratios, or research citation counts. While some of these estimates are more complicated to construct than others, they all require making judgements about things like the value of a human life, the amount of suffering caused by different conditions, or the benefits from a highly cited paper.

The definition of the term risk is tricky to pin down. To some, it’s just a measure of the noisiness of an estimate and is measured using something like the standard deviation. To others, an intervention is only risky when it could potentially underperform some target or cause harm (e.g. downside risk). People seem to use the uncertainty and downside risk terms interchangeably, and I think both are useful, so I include both in my analysis where possible. When I use the term risk below, I’m talking about the standard deviation of the outcome and downside risk refers to the underperformance of the mean.

Here are how the values are calculated:

risk = standard deviation = np.std(series)downside risk (semideviation) = np.sqrt((np.minimum(0.0, series - t)**2).sum()/series.size), wheretis the mean intervention outcome

Finally, how do you determine if there is a return to risk taking? One approach would be to run a linear regression through the data and see if it has a positive slope. This is what I do for most of the sources below, but there’s a problem with this approach. To see why, imagine calculating the cost effectiveness of every possible action, including bogus things like “lighting $1000 on fire”. You’d end up with a lot of useless interventions that would mess up the slope of the linear regression. So another approach would be to just see if the frontier that encloses the top end of the estimates has a positive slope. In Modern Portfolio Theory, this frontier is called the efficient frontier:

I’ve written about this idea before but didn’t have the data to test the concept out until now. I stick with linear regression for this notebook, but I run the data through a portfolio optimization algorithm to create an efficient frontier in my meta-analysis blogpost.

Data Sources

It’s pretty difficult to find datasets that quantify their uncertainty while also using a cross-intervention measure of impact, so it’s taken me awhile to stumble across enough data to complete this analysis. The scrape.py file included in the repo for this projects outlines how I accessed and cleaned data from each source.

All the code and data for this post are available here.

Evidence from Public Policy

First, I look at a dataset from the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP). The WSIPP evaluates evidence based public policies and completes detailed benefit-cost analyses using monte carlo methods. The end result is a list of benefit-cost ratios along with metrics like the chance that the benefit-cost ratio is positive.

The measure of risk I’m using here (the chance costs exceed benefits) sets a really low bar. This ignores the upside of an intervention and much of the downside until the benefit cost ratio is below one. It also counts a project with a very low downside the same of one with only a marginally low downside because they’re just counting up benefit-cost ratios < 1 and dividing by the total number of monte carlo runs. The benefit of this metric is that it is easy to interpret, but I wish they would include a standard deviation as well.

| program_name | benefit_cost_ratio | chance_costs_exceed_benefits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Educator professional development: Use of data... | -174.30 | 69 |

| 1 | Scared Straight | -101.25 | 98 |

| 2 | Behavioral self-control training -BSCT | -80.03 | 77 |

| 3 | Alcohol Literacy Challenge -for college students | -34.25 | 51 |

| 4 | InShape | -29.59 | 53 |

| 5 | Drug Abuse Resistance Education -D.A.R.E. | -7.71 | 51 |

| 6 | Youth advocacy/empowerment programs for tobacc... | -7.13 | 64 |

| 7 | Sex offender registration and community notifi... | -5.14 | 67 |

| 8 | Interventions to prevent excessive gestational... | -5.03 | 64 |

| 9 | Interventions to prevent excessive gestational... | -3.71 | 53 |

| 10 | Police diversion for individuals with mental i... | -2.94 | 99 |

| 11 | Treatment for juveniles convicted of sex offen... | -2.59 | 82 |

| 12 | Project SUCCESS | -1.84 | 61 |

| 13 | "Check-in" behavior interventions | -1.71 | 54 |

| 14 | Opening Doors advising in community college | -1.70 | 78 |

| 15 | Multicomponent environmental interventions to ... | -1.64 | 73 |

| 16 | Inpatient or intensive outpatient drug treatme... | -1.51 | 66 |

| 17 | Domestic violence perpetrator treatment -Dulut... | -1.50 | 77 |

| 18 | Other Family Preservation Services -non-HOMEBU... | -1.40 | 100 |

| 19 | Life skills education | -1.33 | 65 |

| 20 | Intensive supervision -probation | -1.32 | 100 |

| 21 | Even Start | -1.15 | 69 |

| 22 | Family dependency treatment court | -1.11 | 93 |

| 23 | CASASTART | -1.04 | 77 |

| 24 | Cognitive behavioral therapy -CBT for children... | -1.01 | 92 |

| 25 | Cognitive-behavioral coping-skills therapy for... | -0.99 | 58 |

| 26 | Primary care in behavioral health settings -co... | -0.96 | 75 |

| 27 | Community-based correctional facilities -halfw... | -0.71 | 100 |

| 28 | Early Start -New Zealand | -0.49 | 98 |

| 29 | Interventions to reduce unnecessary emergency ... | -0.48 | 52 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 294 | Project EX | 41.71 | 12 |

| 295 | Education and Employment Training -EET King Co... | 41.84 | 0 |

| 296 | Seeking Safety | 42.40 | 12 |

| 297 | Smoking cessation programs for pregnant women:... | 47.61 | 2 |

| 298 | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for adult an... | 48.55 | 15 |

| 299 | Cognitive behavioral therapy -CBT for adult de... | 49.09 | 0 |

| 300 | Cognitive behavioral therapy -CBT for adult an... | 54.01 | 0 |

| 301 | Anti-smoking media campaigns adult effect | 57.07 | 13 |

| 302 | Consultant teachers: Online coaching | 61.94 | 8 |

| 303 | Summer book programs: Multi-year intervention | 63.90 | 30 |

| 304 | Case management in schools | 64.07 | 4 |

| 305 | Good Behavior Game | 65.47 | 30 |

| 306 | Teacher performance pay programs | 65.55 | 12 |

| 307 | Teacher professional development: Induction/me... | 70.72 | 36 |

| 308 | More intensive tobacco quitlines -compared to ... | 73.51 | 0 |

| 309 | College advising provided by counselors -for h... | 74.56 | 0 |

| 310 | School-based tobacco prevention programs | 75.10 | 1 |

| 311 | Cognitive behavioral therapy -CBT for adult po... | 88.11 | 0 |

| 312 | Model Smoking Prevention Program | 89.83 | 9 |

| 313 | Access to tobacco quitlines | 95.85 | 5 |

| 314 | Teacher professional development: Use of data ... | 122.55 | 2 |

| 315 | Tutoring: By peers | 133.59 | 17 |

| 316 | Text message reminders -for high school graduates | 135.71 | 47 |

| 317 | Anti-smoking media campaign youth effect | 147.33 | 0 |

| 318 | Consultant teachers: Content-Focused Coaching | 173.17 | 6 |

| 319 | Summer outreach counseling -for high school gr... | 195.39 | 10 |

| 320 | Alcohol Literacy Challenge -for high school st... | 259.46 | 42 |

| 321 | Text messaging programs for smoking cessation | 363.46 | 0 |

| 322 | Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing ... | 598.94 | 0 |

| 323 | Computer-based programs for smoking cessation | 794.18 | 0 |

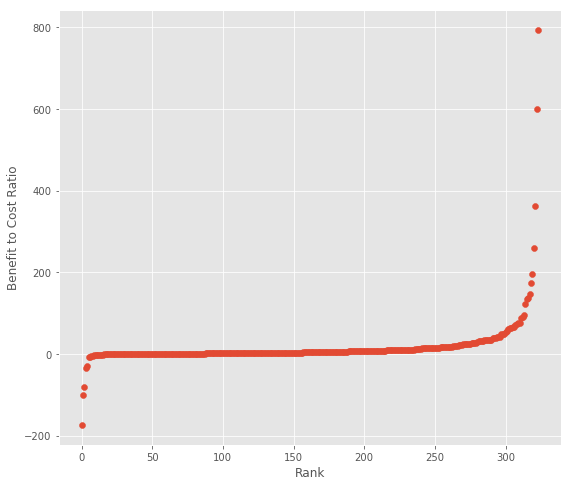

Below is a plot of the intervention rank and the benefit-cost ratio. It’s clear that some interventions outperform others by a few orders of magnitude. Another interesting finding is that the distribution might be two tailed, with some outlying performers on the bad end as well.

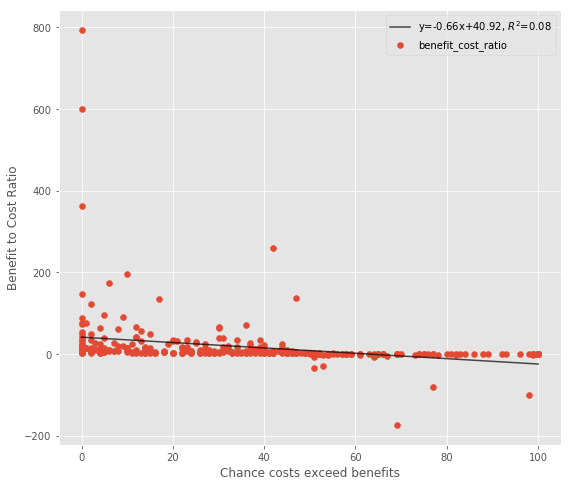

Next, I plot the chance costs exceed benefits (an imperfect proxy for downside risk) against the benefit-cost ratio. I derive the chance costs exceed benefits from WSIPP’s chance benefits exceed costs value, which they calculate by counting results from their monte carlo simulations. This measure doesn’t take into account the scale of good/poor performance, but it’s the best we can get without access to their models.

The end result is that there doesn’t seem to be much of a return to this measure of risk.

Evidence from Public Health

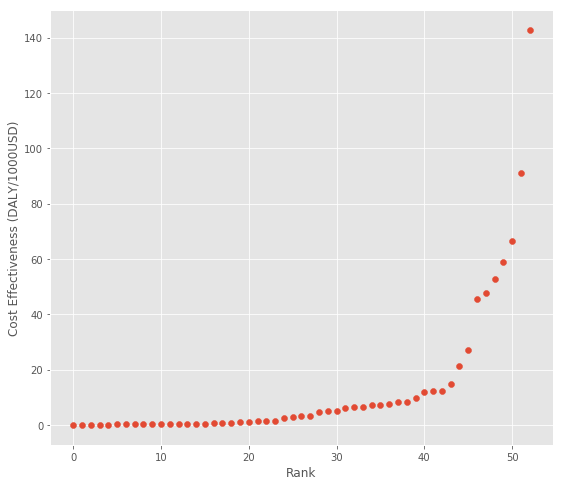

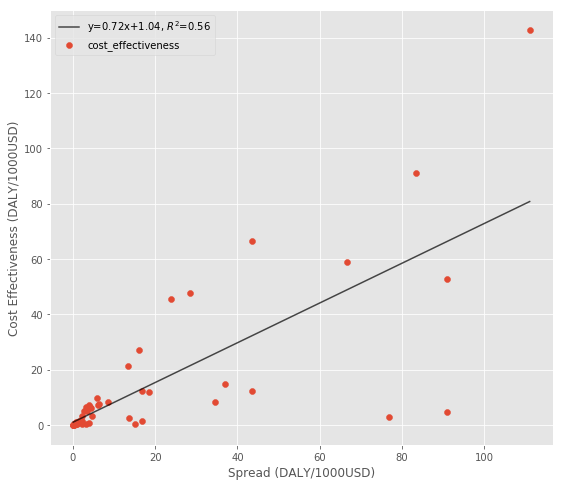

The next dataset I look it is from the Disease Control Priorities Project (DCP2), which comes up with comprehensive estimates of the cost effectiveness of different treatments in developing countries. The original source is a table in the DCP2 report, which Jeff Kaufmann made into a CSV. I selected the interventions with $/DALY units, eliminated any with zero or near zero spread (because they likely came from the same estimate), and only selected the estimates from sub-saharan Africa. Finally I converted $/DALY units to DALY/1000USD so a bigger number has a higher impact.

Using the spread isn’t very rigorous and might bias the results towards understudied areas with few estimates (e.g. an intervention with only a single estimate has spread of 0), but it’s the only measure of uncertainty available here.

| condition | intervention | cost_effectiveness | spread | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | Malaria | Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy... | 142.857143 | 111.111111 |

| 28 | Malaria | Insecticidetreated bednets | 90.909091 | 83.333333 |

| 2 | Lymphatic filariasis | Annual mass drug administration | 66.666667 | 43.478261 |

| 41 | Malaria | Residual household spraying | 58.823529 | 66.666667 |

| 30 | Malaria | Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy... | 52.631579 | 90.909091 |

| 27 | Traffic accidents | Increased speeding penalties, enforcement, med... | 47.619048 | 28.571429 |

| 16 | Lymphatic filariasis | Diethyl carbamazine salt | 45.454545 | 23.809524 |

| 39 | HIV/AIDS | Peer and education programs for high-risk groups | 27.027027 | 16.129032 |

| 52 | HIV/AIDS | Voluntary counseling and testing | 21.276596 | 13.333333 |

| 9 | Tuberculosis (endemic) | BCG vaccine | 14.705882 | 37.037037 |

| 6 | Stroke (recurrent) | Aspirin and dipyridamole | 12.345679 | 43.478261 |

| 14 | HIV/AIDS | Condom promotion and distribution | 12.195122 | 16.666667 |

| 10 | HIV/AIDS | Blood and needle safety | 11.904762 | 18.518519 |

| 18 | Tuberculosis (epidemic, infectious) | Directly observed short-course chemotherapy | 9.803922 | 5.747126 |

| 43 | Emergency medical care | Staffed community ambulance | 8.333333 | 8.403361 |

| 49 | HIV/AIDS | Tuberculosis coinfection prevention and treatment | 8.264463 | 34.482759 |

| 11 | Lower acute respiratory infections (nonsevere) | Case management at community or facility level | 7.751938 | 6.329114 |

| 45 | Problems requiring surgery | Surgical ward or services in district hospital... | 7.352941 | 6.134969 |

| 15 | Diarrheal disease | Construction and promotion of basic sanitation... | 7.092199 | 3.861004 |

| 0 | Congestive heart failure | ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker, with diuretics | 6.666667 | 4.048583 |

| 48 | HIV/AIDS | Treatment of opportunistic infections | 6.410256 | 3.257329 |

| 51 | Lymphatic filariasis | Vector control | 6.250000 | 4.273504 |

| 38 | HIV/AIDS | Mother-to-child transmission prevention | 5.208333 | 2.702703 |

| 32 | Tuberculosis (epidemic, latent) | Isoniazid treatment | 5.076142 | 3.300330 |

| 37 | Tuberculosis (epidemic) | Management of drug resistance | 4.830918 | 90.909091 |

| 17 | Tuberculosis (endemic, infectious or noninfect... | Directly observed short-course chemotherapy | 3.322259 | 2.141328 |

| 36 | Tuberculosis (endemic) | Management of drug resistance | 3.144654 | 4.524887 |

| 24 | Neonatal mortality | Family, community, or clinical neonatal package | 2.898551 | 76.923077 |

| 1 | Alcohol abuse | Advertising ban and reduced access to beverage... | 2.475248 | 13.513514 |

| 23 | Alcohol abuse | Excise tax, advertising ban, with brief advice | 1.584786 | 16.666667 |

| 7 | Ischemic heart disease | Aspirin, betablocker, and optional ACE inhibitor | 1.453488 | 2.105263 |

| 20 | Panic disorder | Drugs with optional psychosocial treatment | 1.362398 | 1.428571 |

| 33 | Coronary artery disease | Legislation substituting 2% of trans fat with ... | 1.193317 | 0.781861 |

| 5 | HIV/AIDS | Antiretroviral therapy | 1.084599 | 0.874126 |

| 8 | Parkinson's disease | Ayurvedic treatment and levodopa or carbidopa | 0.883392 | 1.315789 |

| 22 | Alcohol abuse | Excise tax | 0.726216 | 3.921569 |

| 19 | Depression | Drugs with optional episodic or maintenance ps... | 0.588582 | 0.479846 |

| 25 | Stroke (ischemic) | Heparin and recombinant tissue plasminogen act... | 0.505817 | 0.715820 |

| 44 | Ischemic heart disease | Statin, with aspirin and betablocker with ACE ... | 0.493097 | 3.039514 |

| 40 | Stroke and ischemic and hypertensive heart dis... | Polypill by absolute risk approach | 0.469925 | 0.369004 |

| 21 | Traffic accidents | Enforcement of seatbelt laws, promotion of chi... | 0.408330 | 0.344828 |

| 50 | Dengue | Vector control | 0.389712 | 0.871840 |

| 13 | Diarrheal disease | Cholera or rotavirus immunization | 0.368732 | 2.183406 |

| 42 | Epilepsy (refractory) | Second-line treatment with phenobarbital and l... | 0.330360 | 15.151515 |

| 34 | Bipolar disorder | Lithium, valproate, with optional psy-chosocia... | 0.321234 | 0.813008 |

| 26 | Diarrheal disease | Improved water and sanitation at current cover... | 0.238949 | 0.226449 |

| 35 | Bipolar disorder | Lithium, valproate, with optional psychosocial... | 0.226398 | 0.604595 |

| 12 | Lower acute respiratory infections (severe and... | Case management at hospital level | 0.220751 | 0.309789 |

| 46 | Trachoma | Tetracycline or azithromycin | 0.159515 | 0.198689 |

| 3 | Schizophrenia | Antipsychotic drugs with optional psychosocial... | 0.101688 | 0.067912 |

| 4 | Schizophrenia | Antipsychotic drugs with optional psychosocial... | 0.083893 | 0.063975 |

| 31 | Tuberculosis (endemic, latent) | Isoniazid treatment | 0.075999 | 0.134825 |

| 47 | HIV/AIDS | Treatment of Kaposi's sarcoma | 0.019066 | 0.028602 |

These estimates follow a similar pattern to the WSIPP data, with the top interventions a few orders of magnitude better than the worst.

So it seems there might be returns to risk taking when using the spread as the (somewhat imperfect) measure of risk.

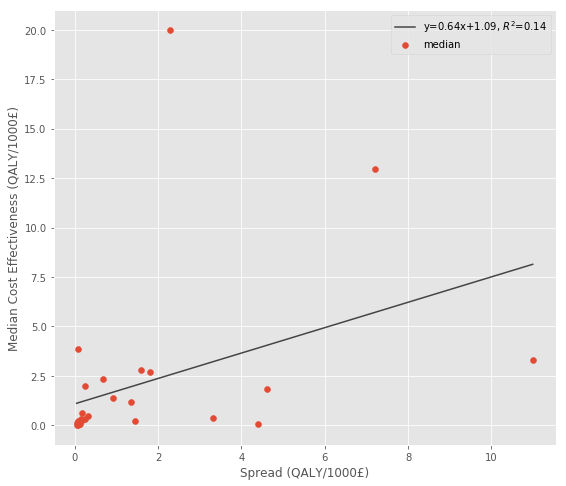

National Health Service

The second dataset I found is from a meta-analysis looking at the cost effectiveness of public health interventions within the English National Health Service (NHS) [15]. This dataset is similar to the DCP2 data above because the only measure of uncertainty is the spread of the estimates. Overall, there seems to be a similar but weaker pattern here:

| guidance_topic | comparator | median | num_estimates | spread | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53 | Smoking cessation—general population: client c... | Background quit rate; no intervention or usua... | 20.000000 | 8.0 | 2.288330 |

| 4 | Exercise prescriptions | Advice | 12.987013 | 4.0 | 7.194245 |

| 56 | Smoking cessation—general population: recruitm... | Background quit rate; no intervention or advice | 3.846154 | 15.0 | 0.074499 |

| 62 | Smoking cessation —general population: dentist... | Usual care | 3.311258 | 3.0 | 10.989011 |

| 51 | Smoking cessation—general population: incentiv... | Intervention no NRT | 2.793296 | 2.0 | 1.597444 |

| 2 | BA (5 min plus self-help) | Background quit rate | 2.702703 | 8.0 | 1.801802 |

| 54 | Smoking cessation—general population: proactiv... | Usual care or intervention but no telephone c... | 2.341920 | 9.0 | 0.683527 |

| 58 | Smoking cessation—general population: identify... | No intervention | 1.984127 | 4.0 | 0.243902 |

| 61 | Smoking cessation—general population: pharmaci... | Usual care | 1.831502 | 2.0 | 4.608295 |

| 0 | BA only (5 min) | Background quit rate | 1.366120 | 8.0 | 0.909091 |

| 46 | PA counselling | No intervention | 1.157407 | 2.0 | 1.353180 |

| 64 | Smoking cessation—disadvantaged groups: client... | No intervention | 0.639386 | 3.0 | 0.166889 |

| 1 | BA [5 min plus nicotine replacement therapy (N... | Background quit rate | 0.473934 | 8.0 | 0.315557 |

| 70 | Smoking cessation—disadvantaged groups: NHS SSS | No intervention | 0.372301 | 2.0 | 3.311258 |

| 71 | Smoking cessation—disadvantaged groups: pharma... | No intervention | 0.317360 | 2.0 | 0.235738 |

| 90 | Screening and BA during GP consultation | No intervention | 0.303030 | 3.0 | 0.151515 |

| 19 | Life-skills training | Normal education | 0.286369 | 3.0 | 0.180180 |

| 74 | Statins—disadvantaged groups: invitation for s... | Usual care or no intervention | 0.230097 | 2.0 | 1.445087 |

| 72 | Statins—general population: pharmacist based | Usual care or no intervention | 0.204415 | 4.0 | 0.151837 |

| 86 | Individual stress management | No intervention | 0.200080 | 3.0 | 0.086498 |

| 87 | Curricular | No intervention or standard education | 0.138889 | 4.0 | 0.093721 |

| 30 | Urban trail | No intervention | 0.095740 | 4.0 | 0.044425 |

| 13 | Brief counselling | Didactic messages | 0.082008 | 2.0 | 4.385965 |

| 11 | Accelerated partner therapy—doxycycline | Patient referral | 0.071301 | 2.0 | 0.106952 |

| 15 | Information motivation and behaviour skills | Didactic information | 0.070706 | 2.0 | 0.129634 |

| 12 | Accelerated partner therapy—azithromycin | Patient referral | 0.051480 | 2.0 | 0.077220 |

| 76 | Advice about PA | Usual care | 0.027855 | 2.0 | 0.051546 |

| 16 | Enhanced counselling | Didactic messages | 0.021927 | 2.0 | 0.083243 |

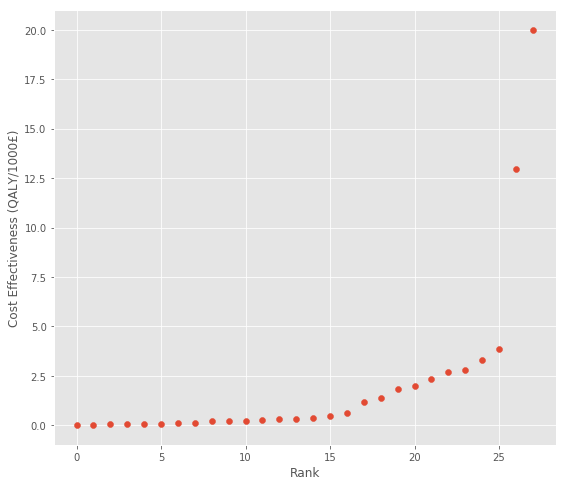

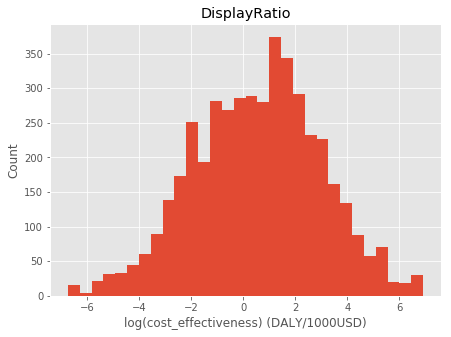

Global Health Cost Effectiveness Analysis Registry

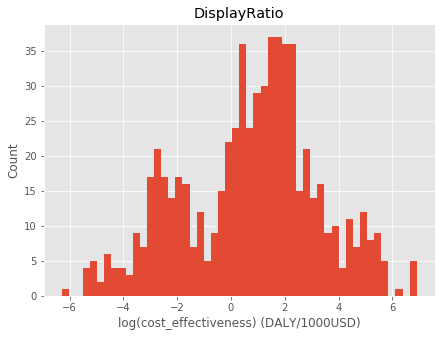

Finally, I look at a massive dataset from the Global Health Cost Effectiveness Analysis Registry (GHCEA). First, I look at the full distribution of cost effectiveness estimates. It’s pretty clear they’re lognormally distributed:

Next, I look at just the estimates that have confidence intervals, which ends up being about 900 out of the 5000 original estimates. The confidence interval column was too erratic, so I went through by hand and found the upper and lower bound. I also filtered out studies with an overall quality rating below 4.5 (on a 1-7 scale). The end result is 653 estimates that have confidence intervals. Here’s a histogram of the filtered results – note that there’s a hole in the distribution where some of the estimates were filtered out:

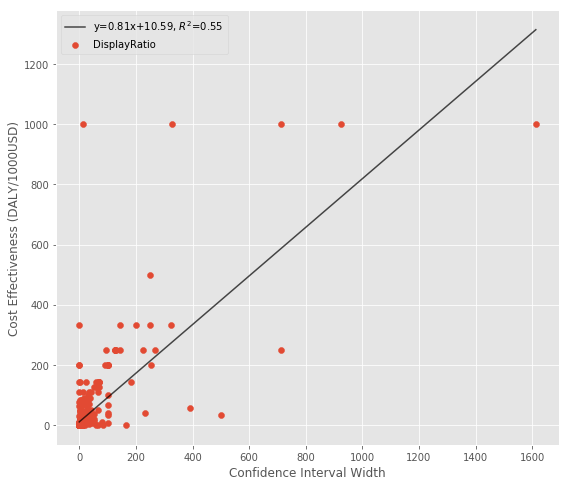

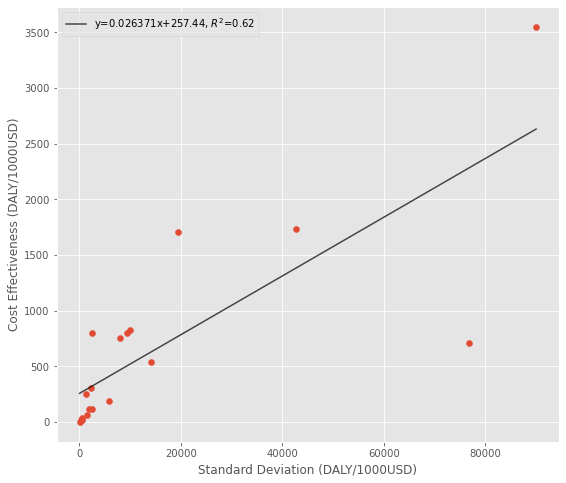

Finally, here’s a scatterplot. It’s not the prettiest relationship in the world, but it does seem to have an upward slope:

Evidence from Philanthropy

GiveWell is an organization that does in-depth charity evaluations, often using cost effectiveness estimates in their decision process. They’ve recently changed their approach to explicitly accommodate different philosophical positions, but the older models had their staff estimate different parameters for direct input.

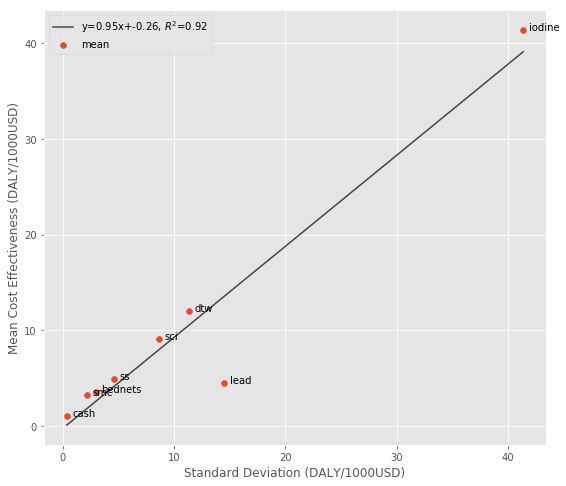

Dan Wahl had the good idea to run a monte carlo simulation by sampling from these staff parameters, which results in a set of estimates you can use to calculate the standard deviation and downside risk for an intervention. I downloaded his code and put the combined outputs into gw_data.csv (see scrape.py), which I include below.

| mean | std | downside_risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| iodine | 41.418910 | 41.364215 | 1.438643 |

| dtw | 12.039437 | 11.307934 | 3.733827 |

| sci | 9.064981 | 8.657475 | 4.589170 |

| ss | 4.894470 | 4.598517 | 6.279625 |

| lead | 4.519663 | 14.533890 | 9.365194 |

| bednets | 3.572679 | 2.964297 | 6.958995 |

| smc | 3.222606 | 2.162316 | 7.082046 |

| cash | 1.060328 | 0.380961 | 8.921943 |

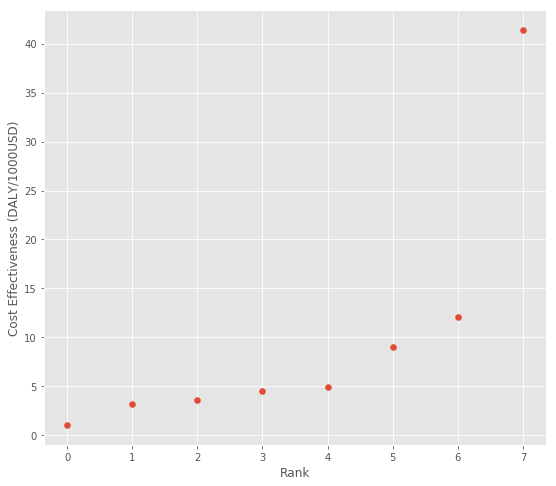

The cost effectiveness rankings here follow a similar pattern to the other datasets, although it’s a little less pronounced:

So if you prefer to use the standard deviation as a measure, there do seem to be returns to risk taking – higher impact estimates tend to be noisier. But if the downside risk metric makes more sense to you, the highest impact estimates underperform the mean less often, so there’s not a return to this measure of risk.

Evidence from Scientific Research

I have two sources of data on the impact of scientific research. The first is from the Future of Humanity Institute’s (FHI) research looking at the long term impact of neglected tropical disease research. The second is data I collected from Google Scholar on the variation in citation counts vs. mean citation counts for individual researchers.

I also found a few related papers in the existing “Science of Science” literature, and summarize those at the end.

FHI Estimates

These numbers differ from the GiveWell numbers above because they are estimates of the value of scientific research, and aren’t derived from randomized control trials of existing treatments. This means we should be much more uncertain about this model and the inputs.

| group | disease | mu | sigma | median | mean | stdev | downside_risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Diarrhoeal disease | Diarrhoeal diseases | -1.466692 | 4.391203 | 0.230687 | 3549.783221 | 89983.188002 | 633.718520 |

| 14 | Meningitis | Meningititis | -2.503745 | 4.463425 | 0.081778 | 1732.527683 | 42673.055643 | 642.757711 |

| 11 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Leishmaniasis | -3.706662 | 4.721702 | 0.024559 | 1703.723172 | 19374.995032 | 645.685782 |

| 17 | Leprosy | Leprosy | -5.014960 | 4.843504 | 0.006638 | 824.521890 | 10050.747664 | 651.870754 |

| 13 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Trypanosomiasis | -5.296044 | 4.895739 | 0.005011 | 802.785665 | 9413.161293 | 652.616249 |

| 1 | Malaria | Malaria | -3.161076 | 4.437962 | 0.042380 | 801.655755 | 2457.881370 | 646.632072 |

| 16 | Meningitis | Multiple salmonella infections | -1.895189 | 4.127971 | 0.150290 | 753.616047 | 8048.560866 | 640.784014 |

| 15 | Meningitis | Typhoid and paratyphoid fever | -2.798470 | 4.327229 | 0.060903 | 709.092672 | 76791.444201 | 645.379213 |

| 12 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Chagas disease | -4.955053 | 4.740730 | 0.007048 | 534.967344 | 14100.186942 | 652.133687 |

| 0 | HIV | HIV | -3.783888 | 4.358867 | 0.022734 | 303.678832 | 2298.067782 | 650.700399 |

| 6 | Helminths | Trichuriasis | -1.937768 | 3.863822 | 0.144025 | 251.336051 | 1374.641439 | 644.123568 |

| 5 | Helminths | Ascariasis | -1.894481 | 3.776170 | 0.150396 | 187.775769 | 5743.164462 | 645.026396 |

| 4 | Helminths | Hookworm | -2.221467 | 3.745220 | 0.108450 | 120.526560 | 2534.843173 | 648.701035 |

| 2 | TB | TB | -3.587428 | 4.086304 | 0.027669 | 116.922570 | 1920.355439 | 651.878971 |

| 7 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Lymphatic filariasis | -2.843354 | 3.724580 | 0.058230 | 59.913072 | 1582.603743 | 651.768843 |

| 8 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Schistosomiasis | -3.354314 | 3.742827 | 0.034933 | 38.477140 | 414.677808 | 653.955657 |

| 9 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Onchocerciasis | -4.002002 | 3.718195 | 0.018279 | 18.365718 | 429.236723 | 655.572266 |

| 18 | Trachoma | Trachoma | -3.984676 | 3.693719 | 0.018598 | 17.066256 | 340.242497 | 655.681808 |

| 10 | Parasitic and vector diseases | Dengue | -5.767322 | 3.092770 | 0.003128 | 0.373548 | 14.685043 | 659.062757 |

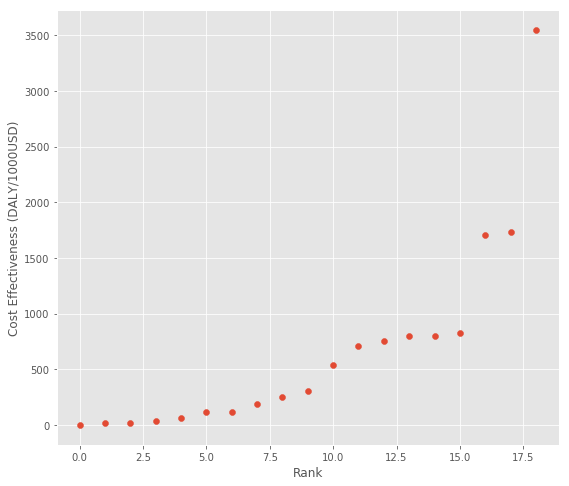

Again, these numbers follow the patterns of earlier estimates with some research topics substantially outperforming others:

So while there is a strong positive relationship between uncertainty and impact, there is a weaker negative relationship between downside risk and impact.

Research Citation Counts

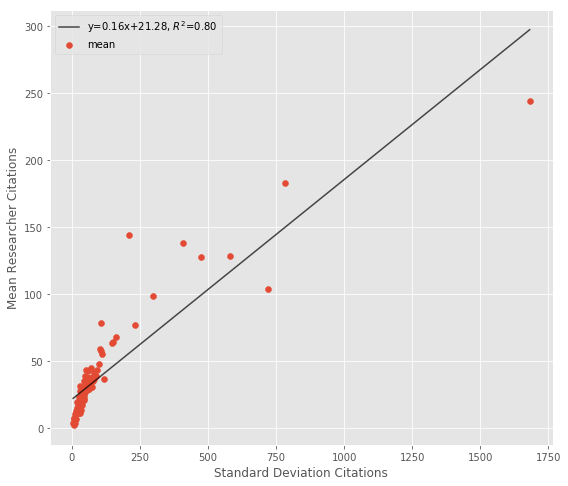

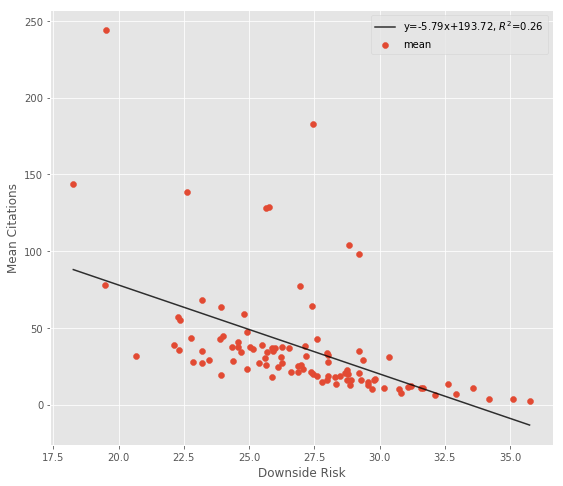

Next, I thought it would be interesting to see if these patterns appear in researcher citation counts. I found a list of ecology researchers along with links to their Google Scholar profiles on GitHub. I treated this list as a population of researchers (I’m not sure if it really is), then randomly selected 100 non-students and downloaded their list of publications and citation counts. I then calculated the mean citation count, standard deviation, and downside risk for each researcher.

The assumption here is that citation count is proportional to real world impact. Another thing to mention is that these scientists have different funding levels, so we don’t know the true funding to citation conversion rate.

| mean | std | downside_risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| id | |||

| 30 | 78.092593 | 107.506958 | 19.496066 |

| 89 | 19.361702 | 17.013327 | 23.927285 |

| 129 | 17.962963 | 20.803996 | 25.888243 |

| 143 | 12.964286 | 19.114629 | 29.574690 |

| 145 | 3.500000 | 4.485018 | 34.183520 |

Using the standard deviation in a situation like this doesn’t make a lot of sense. By default, a very successful researcher might have a higher standard deviation in their citations as they progress through their career [10]. I think the downside risk metric is more useful here, and it shows that highly cited researchers outperform the mean researcher more often.

Uncertainty in Peer Review

An alternate way to look at this question would be to try to relate peer reviewer uncertainty with eventual citation counts. At least theoretically, it could be rational to fund a study with a lower mean reviewer score if there is sufficient uncertainty [11]. While some research has found a positive relationship between mean reviewer score and eventual citation counts [12], and others have studied the variation in reviewer scores [13], nobody has related the variation in reviewer scores with eventual citation counts. I contacted the NIH and they don’t keep a record of individual reviewer scores for privacy reasons, so this type of study doesn’t seem possible currently.

Surprise as Risk

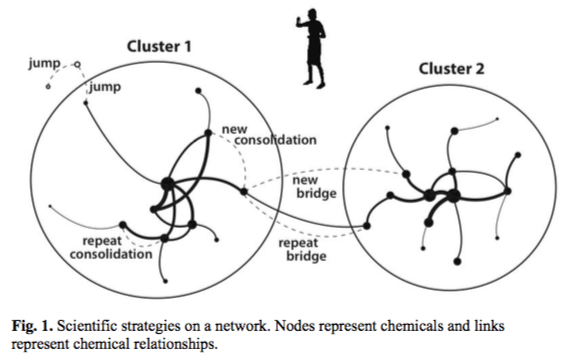

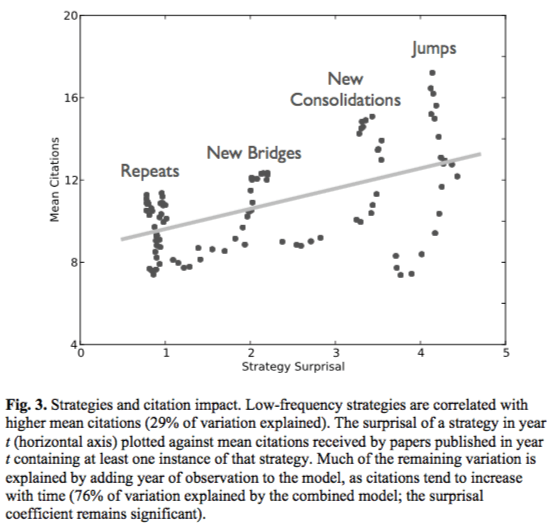

Another fascinating study takes a different approach by measuring if the subject matter of the paper is risky/surprising [14]. They do this by comparing the chemicals discussed in the paper with an existing network of chemical knowledge. Studies that propose a new type of connection or a jump to new knowledge are judged to be more risky (Figure 1), and are eventually associated with higher citation counts and more scientific awards (Figure 3).

The effect size in this paper isn’t huge – a research strategy that is an order of magnitude less probable receives 2.26 more citations on average. But I think this paper gets closer to measuring the concept of scientific risk than anything else. They also conclude that a scientist trying to maximize citation count would probably focus on repeat projects, so specific policies to encourage higher risk science might be needed.

Conclusion

It’s interesting to see some common patterns emerge across these different domains and datasets.

- First, the impact distributions make it clear that some interventions are much better than others. As a result, it makes sense to spend a lot of time searching for good opportunities.

- Second, interventions with a high downside risk tend to have lower expected impacts. Even though high impact interventions are more uncertain, they dip below the mean less often or to a lesser extent. This is actually a good thing because it means there isn’t a huge downside to pursuing the high impact opportunities, at least in this dataset.

- Third, there do seem to be returns to risk (uncertainty), so a large error bound on a cost effectiveness estimate shouldn’t be disqualifying on it’s own.

Whether or not there are returns to risk, then, depends on your definition of risk. Using the definitions from the introduction, there do seem to be returns to risk (uncertainty). In other words, uncertainty is something you might have to learn to live with if you want to have a big effect on the world.

References

[1] What Are Foundations For? Boston Review. http://bostonreview.net/forum/foundations-philanthropy-democracy

[2] Hits-based Giving. Open Philanthropy Project. https://www.openphilanthropy.org/blog/hits-based-giving

[3] Broad market efficiency. GiveWell. https://blog.givewell.org/2013/05/02/broad-market-efficiency/

[4] The Confusion of Risk vs. Uncertainty. The Guesstimate Blog. https://medium.com/guesstimate-blog/the-confusion-of-risk-vs-uncertainty-1c6cd512aa69

[5] Benefit-Cost Results. Washington State Institute for Public Policy. http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost

[6] Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (DCP2). http://www.dcp-3.org/dcp2

[7] GiveWell’s Cost-Effectiveness Analyses. GiveWell. https://www.givewell.org/how-we-work/our-criteria/cost-effectiveness/cost-effectiveness-models

[8] Stochastic Altruism. https://danwahl.github.io/stochastic-altruism

[9] Uncertainty Quantification. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty_quantification#Sources_of_uncertainty

[10] Quantifying the evolution of individual scientific impact. http://science.sciencemag.org/content/354/6312/aaf5239

[11] Improving the Peer review process: Capturing more information and enabling high-risk/high-return research. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048733316301111

[12] Big names or big ideas: Do peer-review panels select the best science proposals? http://science.sciencemag.org/content/348/6233/434

[13] Peer Review Evaluation Process of Marie Curie Actions under EU’s Seventh Framework Programme for Research. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4488366/

[14] Tradition and Innovation in Scientists’ Research Strategies. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0003122415601618

[15] The cost-effectiveness of public health interventions. Journal of Public Health. https://academic.oup.com/jpubhealth/article/34/1/37/1554654

[16] The Global Health Cost Effectiveness Analysis Registry Tufts University. http://healtheconomics.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/ghcearegistry/